There’s this old saying: “It’s not the arrow, it’s the Indian. In photography, we’ve updated it to something safer, but the idea is the same: It is not the camera. It is the photographer.

A guy with cameras made of trash

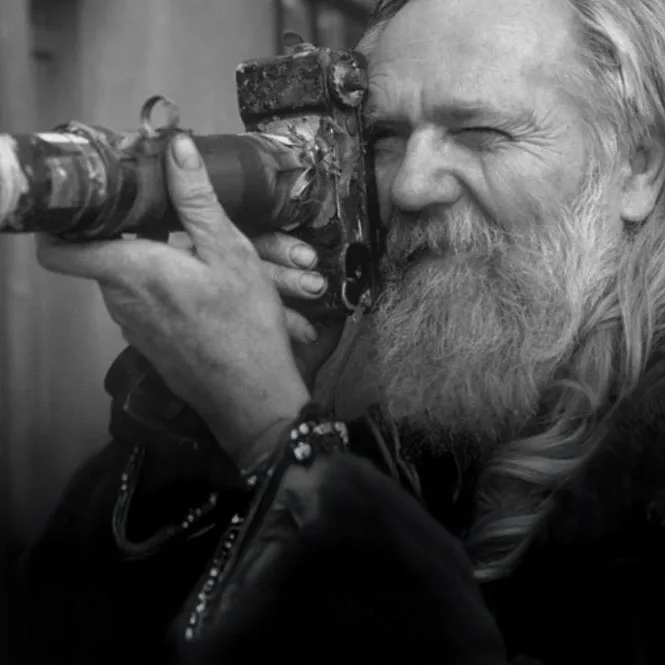

Decades ago, in a small Czech town, there was this strange man walking around in torn clothes, with a wild beard and a homemade camera that looked like it had survived a house fire: Miroslav Tichý.

He built his cameras out of cardboard, scrap metal and old lenses. No Leica, no Hasselblad, no perfect glass. Literal garbage.

With those Frankenstein-cameras he obsessively photographed women in the streets and parks—sunbathing, walking, smoking. The images were soft, scratched, badly framed, “incorrect” by every technical standard we’re supposed to worship. And yet, they had this haunting, dirty, uncomfortable beauty.

To Tichý, the flaws weren’t mistakes; they were the art.

You can (and should) question his ethics. He was accused as voyeur, and to don’t ask for permission to the subects to be photographerd. But you can’t deny this: he proved that a broken tool in the right hands can produce images the “perfect” camera crowd will never touch.

It’s never been about the tool

Today the new “trash camera” is AI. People are acting like the tool itself is evil.

They talk about AI like it sneaks into your house at night, steals your soul and spits out JPEGs. But AI is exactly what cameras, brushes, Photoshop and darkrooms always were: Just another tool.

You can use AI to generate lazy, empty images that look like every other soulless thing in the feed.

Or you can use it the way a real photographer uses anything: as an extension of your taste, your eye, your obsessions, your ethics.

The problem isn’t the tool. The problem is who’s holding it and what they’re trying (or not trying) to say.

Tichý with a cardboard camera is more artist than a gear-obsessed shooter with a $6000 body and nothing to say. The same way a thoughtful creator using AI to push their vision is more artist than someone with a “perfect” setup reproducing clichés on autopilot.

The real job of an image

Somewhere along the way, a lot of photographers forgot what an image is actually supposed to do.

The goal is not:

- to be technically perfect

- to satisfy the pixel peepers

- to get approved by the algorithm

The purpose of an image is brutally simple: A picture should make you feel something. You love it. You hate it. You’re angry, aroused, disturbed, confused, fascinated. You argue with it. You can’t get it out of your head. And if is there, the message has arrived to its destination.

©Miroslav Tichý

There is nothing wrong with that. In fact, that’s the whole point.

What is wrong?

- Indifference.

- The dead zone.

- The scroll-past-without-a-second-look.

If your work doesn’t move anyone, if it leaves people numb, if it never risks anything –

then it doesn’t matter if it was shot on a Phase One, an iPhone, or summoned by an AI prompt. Beautifully produced indifference is still bad art.

John E. Powers already knew this in 1880

This isn’t a new idea invented by “edgy” marketers on TikTok. Back in the 19th century, John Emory Powers, often called the father of modern creative advertising, understood something radical for his time:

The job of a message is to be remembered. It should provoke a strong reaction—love or hate, but never indifference.

He wrote ads that people argued about. Some hated them, some loved them—but they noticed them. They felt something.

That’s exactly what good photography—and good erotic imagery, especially—should do.

If your photo is “nice”, “cute”, “fine”, “well executed”… and that’s it?

You’ve just created background noise. And the world already has enough of that.

AI won’t save you. Gear won’t save you.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth no one wants to hear:

- A better camera won’t fix a boring eye.

- More megapixels won’t fix cowardice.

- AI won’t fix the fact that you don’t know what the hell you want to say.

You can hand the same AI model, the same prompt space, to a tourist and to an seasoned artist

One will produce something instantly forgettable. The other will wrestle with it, bend it, break it, mix it with real images, scars, history, desire – until it becomes something that actually hits you in the gut.

The difference isn’t in the interface. It’s in the human being behind it.

Tools are neutral. Vision is not.

So what really matters now?

If you’re a photographer terrified of AI, here’s the question you should be asking yourself:

“If all my gear disappeared tomorrow, if all I had was a cheap camera…

or an AI interface… would I still know what I want people to feel when they see my images?”

If the answer is yes, you’re fine.

You might be pissed off by the changes, but you’ll adapt.

Because you’re not married to the tool. You’re married to your vision.

If the answer is no, then the problem isn’t AI. The problem is you’ve been hiding behind the camera for too long. Great art has always come from the same place: a human being willing to put something real on the line.

In the end, whether you’re holding a cardboard camera, a top-of-the-line mirrorless, or a keyboard feeding prompts into a model, the rule doesn’t change:

It’s not the arrow.

It’s not the camera.

It’s not the AI.

It’s the damn artist.

Make people feel something—or don’t bother.

©2025 Copyright Alex Manfredini